Importance of Investing

You (hopefully!) have a job and are making money. You may have some extra money if you're careful with your spending habits. There are a few options for what to do with this extra money. You could put it under your bed, or you could park it somewhere else. There are two problems with the bed option: 1) inflation and 2) lazy money.

Let's talk about inflation first. Inflation means that your money actually loses value as time goes on. Remember when a can of Coke was a buck and now it's a $1.50? That's inflation at work. A dollar was good for a whole Coke a few years ago, but now it's only good for 2/3 of a Coke. If you kept your money under your mattress for 10 or 20 years, the purchasing power (i.e. how many Cokes you could buy with the same dollar) would continue to go down. In the past two decades, inflation in the US and Canada has averaged 2% per year. Meaning that if a Coke cost $1 one year, it would cost $1.02 the next and, in 20 years, the same can would be expected to cost $1.50.

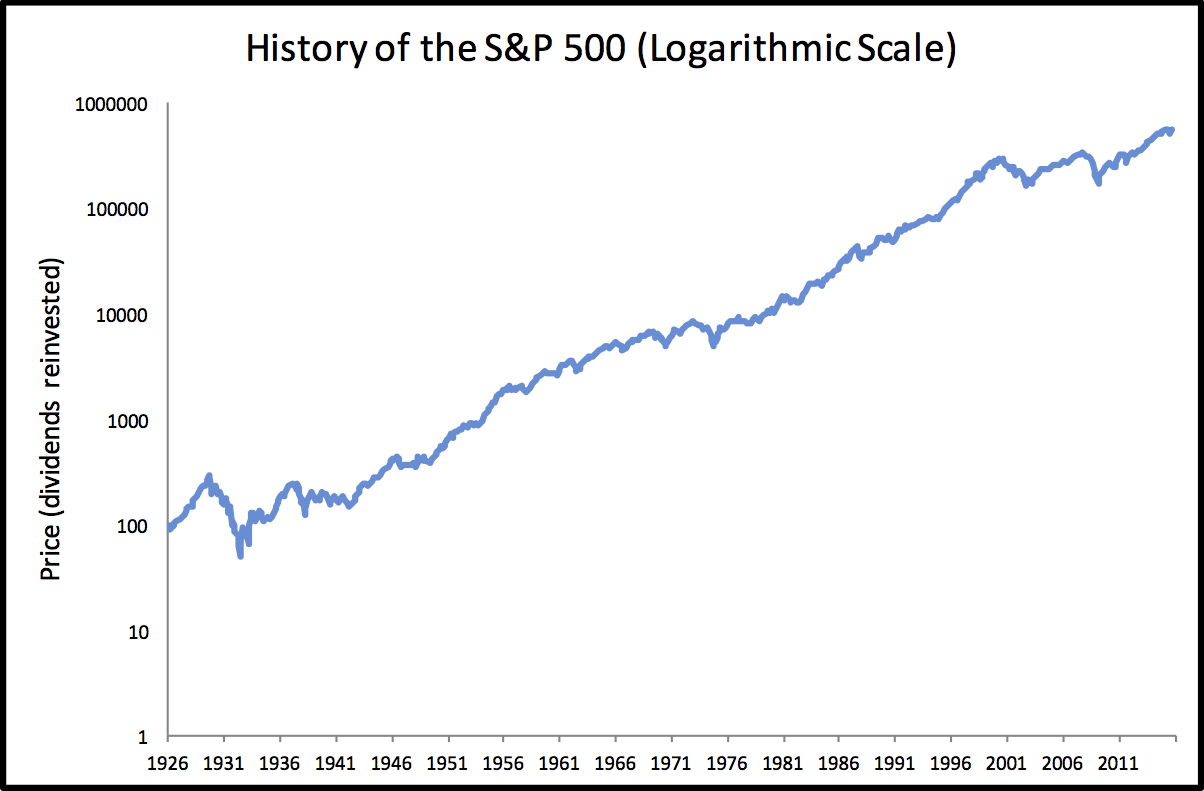

Now let's talk about lazy money. No one likes being lazy, and you shouldn't want your money to be lazy either. Money can do work for you. It can do this work by being invested in financial assets like stocks or bonds. We'll talk about what these are later, but the main point is that money can be put somewhere else other than under your mattress so that it can grow at a rate that's higher than inflation, and hopefully even more than that.

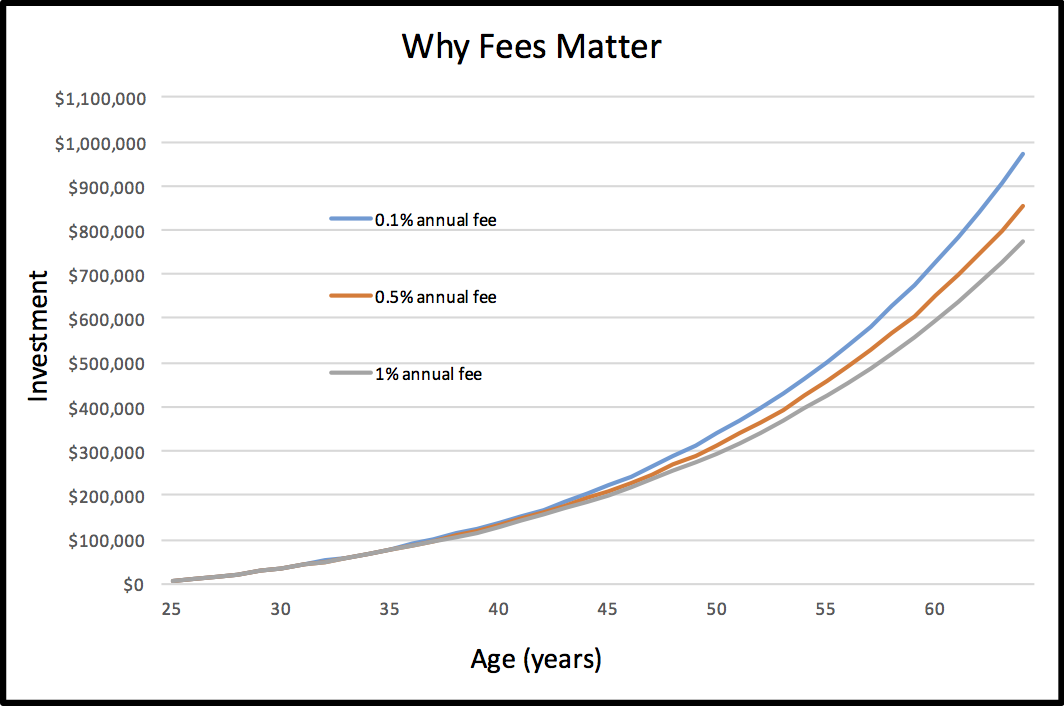

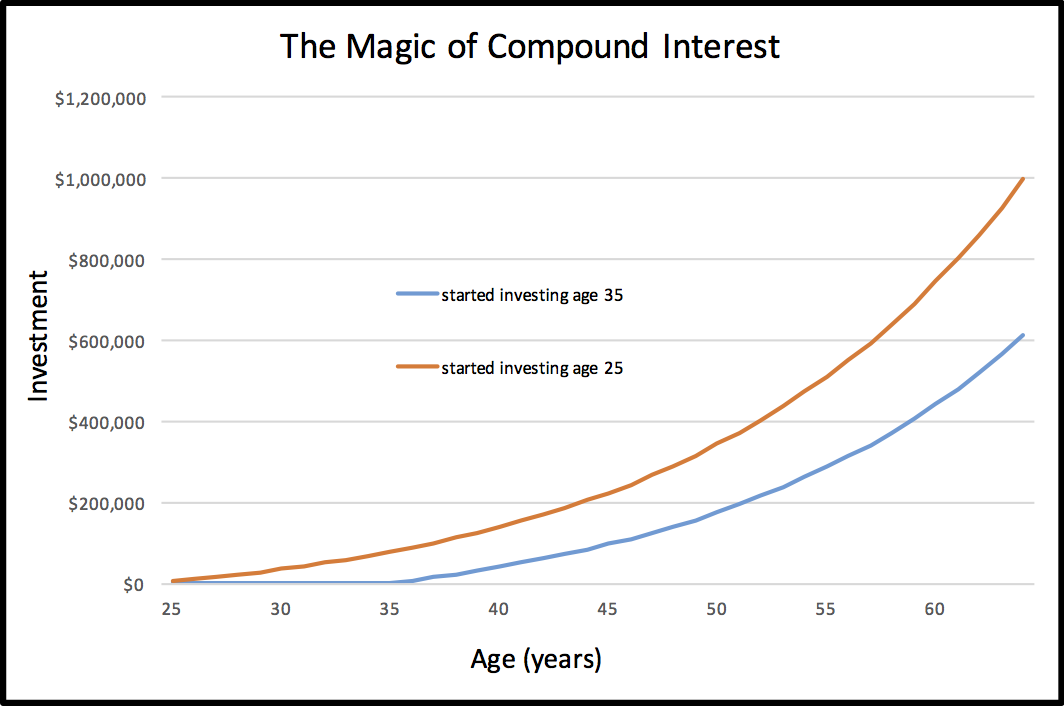

To make this money grow as fast as possible, it's important to start investing as soon as possible. This is because of the magic of compound interest: money that has has been invested longer will make you more money. For example, the graph below shows the investments from two individuals, one who started investing $5,000 per year at age 25, and the other who started investing $7,000 per year at age 35. We assume that they made 7% per year on their investments. Each invested almost exactly the same amount; however, as you can see, the one who invested earlier has almost double the amount of money when they are both ready to retire at age 65.

Why invest in the first place though? Why not use all your extra money to buy chocolate or gold-rimmed lamp shades? Sure, you could do that, but some people would like to retire, and having the option to retire earlier is a nice thing to have. This concept has sexy acronyms like FIRE (for Financial Independence Retire Early) and is taking over the blogosphere. By making your money grow as fast as possible, you can retire earlier than if it just sat around with your lost socks.